In 1998 THE BIG LEBOWSKI planted the idea in my head that it’d be more fun to be poor in Los Angeles, and that would prove to be true. My roommate from Emerson College had driven out to Los Angeles a couple of years earlier and had hit a bump on the road. Christopher knew in July of that year that he wasn’t going to make September’s rent. He worked part-time in the medical props department of ER and the hiatus meant high temperatures and a paycheck drought.

When my phone rang I was across the country in New Jersey working part time, noodling on some writing, but spending most of my day reading comics and playing video games. Before I hung up I’d agreed to rent the second bedroom in his apartment off Melrose. I was met at Los Angeles International Airport by my once and future roommate. I had a bag of clothes, a couple of comics and three hundred bucks in my wallet.

We went straight from the airport to a place he frequented because it served buck and a quarter buds. It took a beer or two to realize I was standing in Hollywood Star Lanes, the bowling alley from Lebowski. It was more than just a bowling alley, it was a wonderful neighborhood dive. That place is just an old memory now.

My first night was the first of many great times in Los Angeles, but the truth is, it was also a hard damn start.

My first bed was an air mattress with a slow leak. By morning I would wake up with my ass on the hardwood floors and my arms up above my body like I was in a hot dog bun. I walked up and down Melrose avenue filling out applications wherever I saw a HELP WANTED sign.

Bill Liebowitz at Golden Apple Comics tried me out for two weeks, and I was almost an Angeleno.

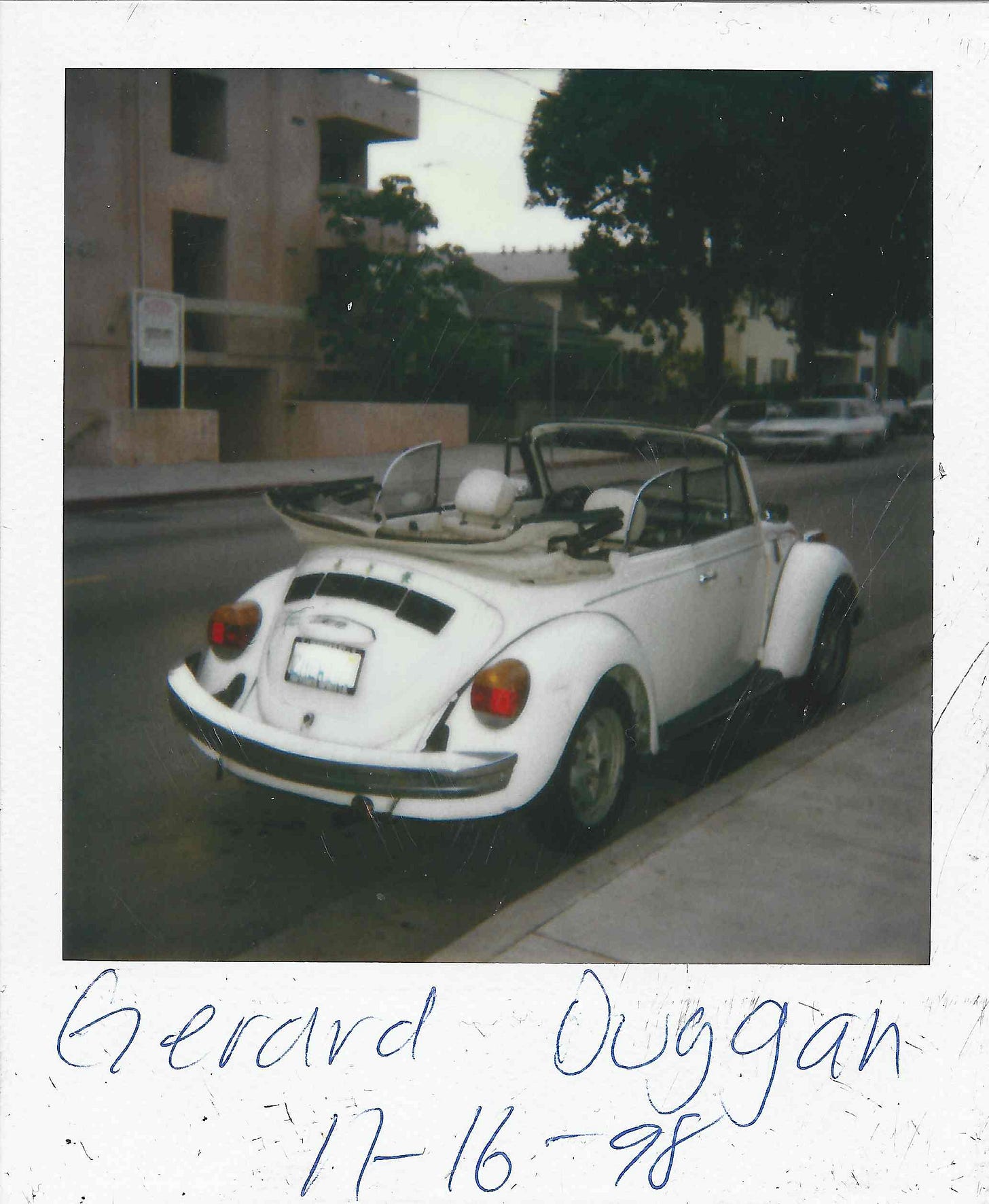

Eventually I put together enough to buy a car that mostly ran. It was a late model Super Beetle and the owner ran the wrong phone number in the Auto Trader. The man on the other end of the line was exasperated.

“I don’t have a bug for sale, sorry!” was the brusk greeting to the quick call.

So I started dialing different versions of the last four digits of the printed number until I hit pay dirt. The owner was surprised I was the only interested buyer. The car was priced to move. I opted not to tell her the truth in case she was hoping for a bidding war. I used every dollar I had to buy the convertible. The roof leaked in the rain, the engine leaked when it ran, but I was finally in business.

Los Angeles cabs were not easy to sort. You needed to call, and then wait. This was years before ride-sharing services. In those years you simply couldn’t live in Los Angeles without a car and a Thomas Guide on the front seat.

The car had character, and with it, I became an Angeleno. The passenger door had a habit of swinging open on left turns. I was flat broke for a while after the purchase. These were tough days and not everything was always working. Not the car, and not the writing.

In the days following the purchase, a friend of mine asked me to a dinner with some old family friends. Robert Forster was going to be there, and I was a big fan. I think it was someone’s birthday? The offer put me in a jam. I could say no, and never meet one of my favorite actors. Or say, yes and risk splitting a pricy dinner bill with no money on my debit card.

I lied and said I had work, but suggested a compromise: Could I drop by for coffee and desert?

My friend agreed, and I ended up having a great time seated across from Mr. Forster. He asked that I call him Bob. When he heard I was a writer that was new to town, he sat up and engaged me like I was the most important writer in town.

“Study the old ones.” he said.

I mentioned some of my favorite films, like THE PARALLAX VIEW, and ALL THE PRESIDENT’S MEN, and he liked those fine, but he was talking about the old, old ones. The conversation moved back in time through cinema history. We talked about POINT BLANK, and the post-war noirs like THE THIRD MAN. Bob respected writing, and writers.

“We don’t have a business without you.” is another line that still rings in my ears. He had decades of experience, and his own ups and downs, and was humble about where his career was before JACKIE BROWN walked into his life.

The restaurant was closing up, and the bill came. Bob wouldn’t let anyone else touch it. I left that table richer than I was, and I think it was a tune-up for my worth ethic as well. I finished scripts faster. I’d already had my share of experiences in Los Angeles that were the antithesis of coffee with Bob. Being at a party and having people walk away mid-sentence upon realization that I couldn’t further their ambitions.

Two decades later I was invited to help Jonah Ray write his host copy for The Saturn Awards. That evening David Lynch was being honored for TWIN PEAKS: THE RETURN.

Forster was having more late-inning success with the chance to play the role of sheriff that Lynch intended him to play when the series debuted in 1990. Backstage I got to reintroduce myself, shake his hand again and say:

“Mr. Forster, thank you. You were very kind to me while I was getting my sea legs under me here in town. You helped inspire me to double down on what was important: my writing.”

“Glad to hear that, Gerry, and please…call me Bob”.

I spent less than an hour of my life with Bob, but that was enough fuel for me. I didn’t exactly get an early jump on my dreams, but I’m trying to get better as I get older. Through the miracle of everything ever being on YouTube, there’s a very short and wonderful interview with Bob sitting at the very table that Quentin Tarantino would change his life forever. You can hear some of the same things he said to me for yourself. Well worth another moment of your time while you’re here.